by Peter Ratcliffe

Reading the motoring letters in the Sunday Telegraph, I came across something which really brought home how much motoring has changed in this country over the past 50 years.

Mr R.G. of Chesterfield, considering the purchase of a new Toyota Corolla, had heard that ‘its engine was rather noisy’. He was told that this shortcoming was because the car is very low geared and at 80 mph the engine was turning over at 4000 rpm.

Now, some of you will, I know, be able to draw on your driving experiences of 50 years ago, and at least half a dozen of you will remember driving in the thirties when our cars were brand new. However, compared with the changes in our motoring environment since the start of the mooring age, I guess motoring in this country was pretty much the same in the 1950’s as the late 1930’s.

I particularly remember the summer of 1953. At the age of 3 1/2, I was obsessed with cars. My father had just bought a 1938 Standard Flying Fourteen for £100, registration number ADB 346 (see picture). It was, in reality, a rather dreary side valve, run-of-the-mill saloon, but, compared with the 1935 Standard Ten, CAN 788, that it replaced, a very fast, modern car.

Within a couple of weeks of buying our ‘new’ car, the family departed on our annual southwards migration from our home in Manchester to the Sussex coast. At this time, it was generally accepted in our family that a good day’s journey, allowing for meal stops and traffic jams through the centres of innumerable towns, was 100 to 150 miles. Consequently, it was quite unthinkable to reach the South Coast from Manchester within one day. Indeed, when two years later we decided to spend our summer holidays in Cornwall, this was quite clearly a three day journey. At the end of the second day’s travelling, we stayed on a farm somewhere on the Somerset/Devon border. That exhilaration of travelling to foreign lands is still with me. How the world has shrunk in the past 50 years!

I remember so well, back in the summer of 1953, standing behind my father’s driving seat, studying the instruments as we sped along the open stretches of road at 50 or 55 mph and, on occasion, touching 60 when conditions allowed. At this speed we were passing everything else on the road.

On the morning of the second day, we visited some relatives near Oxford, and, keen to impress with his new acquisition, my father took them for a run in the Standard, on a long straight. With a certain reckless determination, he coaxed. the poor old thing, with four adults and three children aboard, up to a speedometer reading of 80 mph, probably a genuine 75 mph. I felt so proud of my dad for the rest of the holiday. I might as well have been driven around in a supercharged Bentley or a new XK 120.

About 25 years ago, I bought a book entitled ‘The Complete Catalogue of British Cars’ by Culshaw and Horrobin. It lists, quite comprehensively, all makes of British motor cars from 1900 to 1976 (the date of publication). What must endear this weighty tome to all genuine anoraks is the inclusion of specification tables for each model. These tables include rear axle ratios.

Now, at 3 1/2, I may have been a precocious little brat, but knowledge of the precise rear axle ratio of the 1938 Standard Flying Fourteen certainly eluded me. I do, however, remember clearly that the poor old thing felt as if it were about to explode at that heady 80 mph. Now, with the help of Culshaw and Horrobin, I can understand why.

The Standard, along with virtually all British cars of the period, had a dismal rear axle ratio of 5.25, equating probably to about 15 mph per 1000 rpm in top. Oh, that poor old plodding side valve engine! It’s amazing that it lasted the five years of my father’s ownership after the caning he gave it.

Of course, the gearing used in cars is influenced by many factors, the type of road conditions available being one of the most important. When open straight roads were and far between, and most journeys involved driving through the congested centres of towns, top gear flexibility was held in much higher esteem than today.

Nevertheless, flicking through my trusty tome, the back axle ratios for 1930’s cars makes depressing reading. Small, high revving cars such as MMM MG’s were invariable geared around 15 mph per 1000 rpm. Less sporting small cars were geared much the same, they just went even slower.

But what about large, high performance cars of the 30’s, cars such as the straight eight Railton; a car boasting a power to weight ratio far in excess of anything else on the road barring out and out sports racers? The standard ratio used on this 4.1 litre car was 4:1 which on 600×16 tyres means about 19 mph per 1000 rpm. The car could pull a very much higher rear axle ratio than this, and I believe the reason it was not employed lies largely in the road conditions for which the car was designed and the 30’s motoring culture of top gear flexibility, avoidance of gear changing, and few opportunities to exceed 60 mph.

Things seem remain much the same through the 40’s and 50’s and cars such as the MG TD were still noisy and stressful at higher cruising speeds on a 5.125 rear axle ratio. When more streamlined forms such as the beautiful MGA were produced, rear axle ratios gradually started creeping up (to be clear, that means a lower number:1-Ed), but it was only when the motorway age dawned and overdrive gearboxes became more popular during the 60’s that this trend really took off and has continued steadily ever since.

Will the trend continue? Well, as power outputs rise and development of diesels with massively higher torque figures tha equivalent petrol engines, whilst engine operating speeds remain roughly the same as they were 30, 40 and 50 years ago, I can’t see the trend towards higher and higher ratios tailing off yet. Large, luxurious sports saloons of the 21st century utilise top gear ratios giving well in excess of 30 mph per 1000 rpm. They can lope along our motorways (contra flows permitting) at 90 mph at less than half their maximum safe revs.

And so we reach the 2003 Toyota Corolla-rather ‘low’ geared at 20 mph per 1000 rpm by today’s standards, but still higher than the highest performance British 4 litre sports saloons of the 1930’s. In other countries, with different motoring conditions, the transition to higher gearing took place rather earlier and in some cases more dramatically. Forgive my mention here of my streamlined, rear engined Tatra 87 of 1937. This 3 litre car has an output of 75 bhp and weighs the same as the SA, but with a final drive ratio of 3.15 the engine would be turning over at just 4000 rpm at the max speed of 100 mph. In the instruction manual there is the solemn note to the effect that maintaining speeds above 88mph for long periods may increase the rate of engine wear-imagine that in your SA! Nowadays, of course, the gearing of the Tatra 87, so exceptional in its day, is about average for a 2 litre family saloon.

How does this all relate to SVW cars? When new, their rear axle ratios of 4.75, 5.22 and 4.78 respectively, were entirely typical of their type of car. All SVW engines in standard tune sound relatively smooth up to 3800 or 4000 rpm but are not really happy above that level for any length of time. The majority of owners seem to cruise at 3000 to 3500 rpm, which equates to 50-60 mph for a VA and 55-65 mph for SAs and WAs.

That’s fine for those of us who only use roads like those for which the car was originally designed, but for the majority of us, our use of the cars nowadays involves some travel on roads specifically designed for high speeds. For instance, over the last few years, we have enjoyed a fantastically successful series of SVW rallies in England, Wales, Germany, Holland and Belgium. Whilst the driving during the rally weekend is usually over quite short distances and along minor, scenic roads, most participants have had to travel considerable distances on high speed roads in order to get to the rally. After a long and eventful Sunday, how many of you can honestly say you didn’t feel a slight touch of envy as modern cars speed past you as you trundle homewards at a steady maximum of 60mph?

What can be done to improve things? There are three options:

- Put up with it. Convince yourself that the low gearing of your car is part of its period charm. Smile as a stream of more modern cars sweeps past you and take more aspirins for your noise-induced headache. Plan your journeys avoiding major roads and never go on a motorway. I personally find this approach valid a lot of the time, but I don’t want it to be my only option.

- Make the engine happier at higher revs. During the last few years, I have been employing mild, standard tuning techniques on SVW engines, not only to give a small power increase, but to improve smoothness in the middle speed range. The result is a sweeter and more willing engine which in turn offers more relaxed cruising. There is a limit, however, to how far one can go with standard tuning techniques on a long stroke relatively slow revving engine from the 1930’s. SVW engines are not as tuneable as the XPAG unit found in later T Types. Furthermore, the tuning approach is really only a viable option if you are contemplating a full engine rebuild.

- Raise the gearing. This may be achieved by changes of gearbox ratios, addition of an overdrive, change of wheel/tyre size, or change of rear axle ratio.

Recently, there has been a lot of interest in the installation of a 5 speed Ford Sierra gearbox in MGs. It makes a lot of sense, so long as originality is not so important to you. So far, I think only XPAG and B series conversions have been done. Who will be the first to try it out on a SVW car? Any offers?

An alternative to a new gearbox is to add an overdrive to the existing gearbox. MGB overdrive units can be made to work very well on MMM cars, but I suspect that quite a lot of butchery would be necessary to the transmission tunnel of SVW’s, as well as the need to shorten the propshaft.

Recently, Joe Potter has fitted a beautiful overdrive conversion to his WA Tickford; a really excellent job. I’m sure it took a lot of thought on the design side, and a lot of money as well! I understand this overdrive raises the gearing a whopping 26% and it will certainly make high speed cruising a very relaxed affair, but I must admit that I rubbed my eyes in disbelief when I first saw two identical gear levers sticking out of the transmission tunnel!

There is little scope for increasing the wheel or tyre size on SVW cars because of clearance problems. VA’s can be fitted with 5.50×19 tyres instead of the standard 5.00×19, but the increase in gearing is only 5%. Its probably worth thinking about if you are fitting a new set of tyres in any case, but the steering will feel a little heavier. Larger tyres on the SA and WA will foul the rear wings and are not a cost effective route to higher gearing.

So that leaves us with the option of changing the rear axle ratio, which has a lot to recommend it.

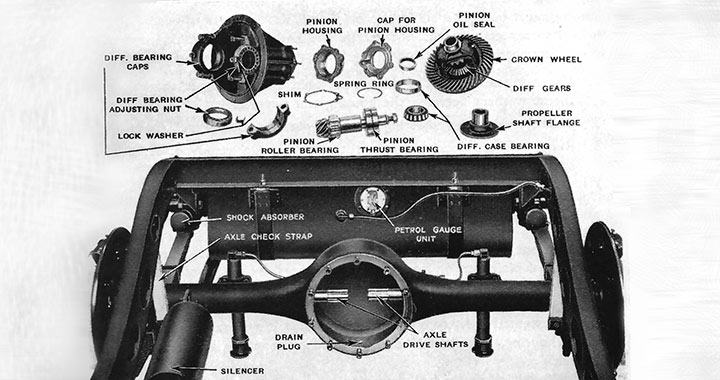

Although Blower quotes alternative axle ratios for SVWs, I’ve never come across any of the original alternatives in an MG casing. The later VA rear axle, however, was essentially the same as that used on the post war Wolseley 18/85 and the rear axle from this car (if you can find one) will provide a 4.8 ratio yielding a worthwhile 8% increase in gearing. Several Vas are being used in the UK with this ratio, and from talking to the owners, and having driven a VA so converted, I get the impression that this ratio is about right for a VA in modern road conditions, offering a worthwhile increase in comfortable cruising speed without seriously compromising acceleration.

Having much greater torque, the SA and WA engines can certainly cope with a greater %age change than this-in the region of 12-15% with no significant impairment of acceleration or hill-climbing abilities. Dave Barker in NZ has gone a little further by fitting a big Healey crown wheel and pinion to his SA-I think the ratio is about 3.9:1. This is a really relaxing car to drive, but I didn’t try it in hilly country. Maybe this ratio, an 18% increase on standard, would also sap some of the car’s acceleration. With the standard engine, but with a slightly tuned one…??

Well, I think I’ve rambled on long enough. Maybe I’ve given you a little food for thought or convinced you that I’m quite mad. Maybe the path to higher cruising speeds lies within ourselves. When I owned a Riley 9 in the 70’s, I knew an old chap called Ron who had owned a near identical car for many years. I got a headache driving mine over 55 mph, it was so noisy, but he drove his at 70 mph with a big grin on his face. What special rear axle ratio did he employ? Then I was told that poor old Ron was really quite deaf.